The Case for a Culture International: Learning from the 20th Century Latin American Left

The resurgent U.S. left needs a cultural strategy. Latin America's Nueva Canción movement can be an important source of inspiration.

Internationalism was key to the success of left-wing movements in the 20th century. As we enter the third decade of a new century, developing a socialist movement based on an international federation of progressive and revolutionary groups, parties, and institutions will be pivotal to re-building global, left counter-hegemony. However, critical discussions of 20th century left-wing movements often leave out a key aspect in the building of socialism: the role played by progressive and revolutionary groups’ support for cultural production. This is not to say that no scholarship has been done on revolutionary culture (i.e. revolutionary artists, their work, and how this work has been used to develop cultural hegemony), but rather, that there has been little writing on the practical strategies that left-wing political groups used to develop institutions of cultural production and distribution, and how this has aided in the historic, internationalist project of the radical left.

As Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) grows in domestic influence and begins to look for international partners with which it can ally, it should also begin to think critically about how to develop counter-hegemonic cultural institutions. Culture, which here includes the whole range of performing, fine, and literary arts, as well as digital and broadcast media, can act as a powerful adhesive for binding international alliances together. Without culture, the counter-hegemony of a political bloc is often fragile. It is in the creation of a common set of aural, visual, and literary references, indeed a popular culture, that the hollow spaces of a movement are filled. In Marxian terms, the base of a mass movement, its scaffolding, is the set of political-economic demands its members hold in common, while its superstructure is the common popular culture that these members share when expressing their demands and solidarity with one another. If culture is not considered as an important part of the superstructure, a mass movement is in a weaker position to either maintain internal cohesion after political defeats, or drive toward assuming political hegemony more generally.

However, culture is more than just a set of aesthetic, moral, and ideological references used in forming collective identity. Culture is a natural resource and a form of human production that creates both ephemeral practices and material goods. Two dominant forms of cultural production have existed in human history. The first is folkloric production. Produced and distributed orally, this form of production is mostly ephemeral and is experienced as a practice or performance. The second form is commodity production, which creates reproducible, physical objects such as books, written and recorded music, instruments, and works of art. Between folkloric and commodity production there is a wide spectrum of mixed forms. For example, a society may have a system of musical production that is folkloric in its production of songs, produced and distributed orally, but commodified in its production of physical musical instruments, produced by craftspeople. Despite its historically being understood as an improvement on nature, culture might be seen as a natural resource created organically by human interaction. It functions as a set of references which human groups can mobilize to create collective identity through the production of ephemera and physical goods.

In modern capitalist society, culture is an entirely industrial operation. Cultural production is specifically geared towards the creation of commodities for exchange on a market. Any left-wing cultural strategy has to understand culture under capitalism as an industry (or group of industries) that exists to create profit for the owners of the means of cultural production. The owners of the mainstream media, the Hollywood film industry, the U.S. recording industry, major private universities, publishing companies, and global fine arts conglomerates are just some of the industries in question. These industries produce commodities which replicate the values of the capitalist class. The ideology around cultural production under capitalism, along with the enormous profits the cultural industries generate, are key aspects that reinforce the capitalist class’ economic and cultural hegemony. An internationalist left-wing cultural strategy must be aware of both how capital is currently organizing cultural production, and how the left has historically mobilized culture at an institutional level. While the history of the 20th century is replete with examples of left-wing cultural mobilization, one of the most successful on an international scale was the pan-Latin American Nueva Canción (New Song) movement.

Nueva Canción and the Latin American Left

Nueva Canción was a Latin American folk music-revival movement that emerged in the mid-1960s and continued through the 1970s and 1980s. Because of its pan-Latin American scope, the style of Nueva Canción artists was incredibly diverse. However, the movement prioritized the inclusion of indigenous instruments, for example, in the case of Chilean artists, filling auxiliary roles usually played by European horns and woodwinds with Andean flutes and panpipes.

Chilean Nueva Canción group Inti-Illimani performing Victor Jara’s instrumental composition “La Partida” live in 1975. The final section of the song features the quena, an Andean flute.

The origin of the Nueva Canción movement can be traced to the efforts of Latin American folklorists in the early twentieth century to study what they understood to be dying cultural forms. For example, many Nueva Canción artists cited the Argentine musician, ethnomusicologist, and Communist activist Atahualpa Yupanqui, who began documenting and performing Andean indigenous music in the 1930s, as a key influence. However, much of the movement’s political momentum can be traced to an explosion of state-sponsored cultural initiatives in Cuba in the aftermath of the Revolution. Castro’s revolutionary government set up a number of cultural institutions, such as Imprenta Nacional de Cuba (National Record Label of Cuba) and Casa de las Americas (Americas House), that were meant to rival U.S. capitalist cultural industries, specifically Hollywood. The term Nueva Trova (New Troubadour) was coined to describe the revolutionary musicians who were supported by these organizations. Silvio Rodriguez and Sara González were just two of the many musicians who received state support for the production and distribution of their work.

In fact, the Cuban government was engaging in an unprecedented cultural project. Before the Revolution, the U.S. had colonized Cuba’s cultural industry by appropriating its domestic culture, commercializing it, and exporting the product back to Cuba. The absence of large scale domestic industries left space for the revolutionary government to develop state-owned institutions that produced cultural commodities as a public good. The Cuban government financially supported culture and distributed it to the public for free as a Cuban citizen’s “social salary.”

“Ojalá” was originally composed by Nueva Trova songwriter Silvio Rodriguez between 1968 and 1970. This 1978 version has become his most beloved recording.

The musical cultures of many other Latin American countries had relationships to the United States that resembled that of pre-Revolutionary Cuba. In the post-World War II period, U.S. record companies had set up large Latin American subsidiaries in Mexico. From this base of operations, these corporations appropriated numerous Latin American musical styles, fused them into a commercialized sound, and flooded domestic Latin American markets with these records. Beginning in the 1950s, Latin American artists across the political spectrum began to lament that domestic musical styles and practices were being erased by the dual pressures of cultural appropriation by the U.S. music industry and its economic colonization of the music market. Traditionalists focused mainly on the former pressure, taking issue with how domestic music was being aesthetically distorted through commercialization. However, left-wing critics understood that the problem was not purely an issue of aesthetic distortion, but chiefly of economic dependence. It was not only the protection of native musical practices that was at stake, but the ability of domestic culture to grow independently of the interests of U.S. capital. For example, Violeta Parra, a Chilean singer-songwriter, ethnomusicologist, and Communist activist, collected and recorded traditional songs, but also demonstrated her awareness of market pressures while composing new songs in a pop style with contemporary arrangements.

While some Nueva Canción artists, such as Parra, had left-wing political beliefs the movement as a whole, made of disparate local scenes in Chile, Argentina, Mexico, and Nicaragua, was not intrinsically left-wing. It was not until progressive and revolutionary groups in Latin America recognized that mobilizing culture on a large, industrial scale could create a critical economic front in the battle against capitalism and mobilized the Nueva Canción movement, that the sound of Nueva Canción became the aural signifier of the Latin American left.

Violeta Parra’s “Gracias a la Vida,” first released in 1967, has since become her most famous song and a Chilean popular music standard.

In 1967, the youth section of the Partido Comunista de Chile (Communist Party of Chile, PCC) established a record company called Jota Jota (JJ, a play on the youth section’s official name, Juventudes Comunistas de Chile, abbreviated as JJ.CC) to release Chilean Nueva Canción group Quilapayún’s second full-length record, X Vietnam. Jota Jota was eventually renamed Discoteca del Cantar Popular (Popular Song Club, DICAP). The concept of a left-wing group starting its own record label was nothing new. DICAP, however, was different in both scale and vision. While most left-wing record companies were small, temporary initiatives created to put out a few recordings of sympathetic musicians or speeches by leftist leaders, DICAP was seen as instrumental for PCC’s contesting U.S. control of the domestic, Chilean, cultural market. Early on, DICAP merged with Violeta Parra’s independent record label Peña De Los Parras, which was associated with the progressive cultural center of the same name that she had founded in the mid-1960s. The label released the early records of Chilean Nueva Canción stars Victor Jara and Inti-Illimani. It set up international subsidiaries in Peru, Uruguay, France, and the Netherlands, established distribution relationships with sympathetic, independent record companies across Latin America, such as Discos Fotón in Mexico and Promecin in Venezuela, and musical solidarity committees in Europe and the U.S., as well as the industrial-scale, state-owned Cuban record conglomerate Empresa de Grabaciones y Ediciones Musicales (Company of Recordings and Musical Editions, EGREM). When the PCC joined Salvador Allende’s left-wing electoral federation, the Unidad Popular (Popular Unity, UP) in 1969, DICAP established a domestic subsidiary of the same name to release a compilation record of UP’s campaign anthems, including “Venceremos.” After the UP won the 1970 Chilean presidential election, DICAP was pressing upwards of 240,000 records annually and their record sales represented a third of the domestic Chilean market.

“Venceremos,” here performed by Quilapayún, was the official campaign anthem of UP. It was composed by Sergio Ortega, a Professor of Music at the University of Chile and activist in the PCC.

Through its international subsidiaries and affiliates, DICAP was able to export the sound of Chilean Nueva Canción to the rest of the world as the global soundtrack of anti-capitalist resistance. Chilean Nueva Canción became a cultural reference point, an adhesive for left-wing groups on an international scale. The sound of the Andean panpipe could be heard at the meetings, parties, pickets, and protests of labor unionists, student activists, communists, socialists, and anarchists around the world– especially in Europe. After the U.S.-backed military coup of 1973, most Chilean left-wing activists were either killed or forced into exile. DICAP was banned in Chile and its administration fled to France. They continued to run DICAP from their French subsidiary, Canto Libre (Free Song). However, their operation became a shadow of its former self.

German pressing of Quilapayún’s Patria LP with the DICAP logo on the bottom right (Courtesy Interference Archive, Brooklyn, NY)

The success of DICAP had ripple effects across Latin America. In Puerto Rico, for example, the Puerto Rican Socialist Party (PSP) established Disco Libre (Free Disc), which released 20 records of popular music over the next decade. These, notably, included the early recordings of Puerto Rican protest singer Roy Brown. DICAP had its most powerful effect, however, on the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (Sandinista National Liberation Front, FSLN) in Nicaragua.

Music played an enormous part of the Sandinista movement from its very beginning. Because the working-class and peasant populations of Nicaragua were largely illiterate, the FSLN used music as one of its main tools of political education. Musically-talented members or sympathetic musicians composed songs on political topics, which most other left-wing groups would distribute in pamphlet form. The FSLN founded Discoteca del Arte Popular (Popular Art Club, DIAP), a record label modeled explicitly on DICAP, in the late seventies to release records by brothers Luis Enrique and Carlos Mejia Godoy, two beloved Nicaraguan musicians who were both dedicated Sandinistas and pivotal in the development of Central American Nueva Canción. DIAP, like DICAP, relied heavily on developing international affiliations with sympathetic independent record labels and musical solidarity committees for their distribution. In the case of DIAP, these international relationships were even more important because the label operated illegally and was unable to expand into the large scale operation that DICAP had been. When the FSLN finally emerged victorious from the long Nicaraguan civil war, the new government initiated a nation-wide cultural program that rivaled the 1930s U.S. Works Progress Administration’s Federal One arts programs in size and scope. This included establishing Empresa Nicaragüense de Grabaciones Culturales (Nicaraguan Company for Cultural Recordings, ENIGRAC) as a state-owned industrial recording conglomerate modeled on Cuba’s EGREM. Like the Andean panpipe before, the sound of the Nicaraguan marimba, notable for its buzzing quality, became a signifier of international anti-capitalist resistance.

Carlos Mejia Godoy y Los de Palacagüina perform “Chilotito Tierno” live at the Concierto de la Paz music festival held in Managua, Nicaragua in April 1983. The song prominently features the Nicaraguan marimba.

The title track of Luis Enrique Mejia Godoy y Mantocal’s 1981 Un Son Para Mi Pueblo. Originally released on ENIGRAC. Distributed in the U.S. by Paredon Records.

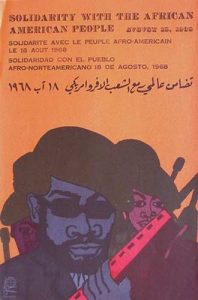

It is important to note that mid-20th century Latin American left-wing cultural mobilization also extended beyond music. For example, in 1967, the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL), a network of anti-imperialist organizations closely affiliated with the Tricontinental Congress and the Cuban revolutionary government, established Tricontinental Magazine. Called a “Bible among revolutionary circles” by Stokely Carmichael, the magazine served as a forum for seminal discussions on culture across the left in Latin America, Africa and Asia, and was unique for its internationalist-themed cover art and inclusion of tri-fold posters, a regular contributor being Black Panther Party Minister of Culture Emory Douglas. With its international distribution, Tricontinental Magazine’s aesthetic production was one of many contemporaneous cultural analogues to the Latin American left’s mobilization of the Nueva Canción movement.

Original illustration by Emory Douglas, poster design by Lazaro Abreau, Solidarity with the African American People, 1968. 33 x54 cm. Offset litho print. (Courtesy OSPAAAL)

These cultural mobilizations were successful in their creation of an international left-wing culture. This was not because of any inherent aesthetic qualities, but because of the nature of their production and distribution. In the case of DICAP specifically, the musicians and organizers involved understood that musical culture was a natural resource with numerous uses. It was a reference point that could be used to develop collective identity, a tool for political education, and, importantly, a commodity that could be sold in a market, though not necessarily the one envisioned by the political consensus in Washington, D.C. By analyzing the ways in which global capital appropriated musical practice, and then produced and distributed it with the dual purpose of generating profit and maintaining ruling-class cultural hegemony, DICAP was able to develop itself into a successful, counter-hegemonic cultural institution that could contest global capital in the Chilean cultural market domestically, and export an international sound of resistance abroad.

Conclusion

These examples are not meant to be taken as a strategic roadmap for the contemporary DSA. Rather, it is meant to show that culture should not be overlooked as a strategically important front in any internationalist, left-wing movement. Without cultural mobilization, we cannot create a sense of internal, collective identity strong enough to survive massive political defeats or internal discord. Nor can we hope to meaningfully develop a hegemony in the domestic population, let alone create an aural, visual, or literary culture that can be used to tie us to our comrades abroad.

Most importantly, by ignoring culture, we retreat from a key economic front in the fight against global capital. In contemporary capitalism, culture is industrialized and is produced as commodities to be sold for profit. Our goal should not be to return to a folkloric mode of production, but to wrench control of industrialized culture away from the ruling class so that it can be operated democratically. While the examples of state-owned conglomerates and recording companies with international distribution may be intimidating, DSA should start small. Jota Jota, DICAP’s predecessor label, began as a tiny operation with a single release. Like them, we should start by thinking locally. The initiation of cultural caucuses in our local chapters, which could hold events as simple as benefit concerts, film screenings, artist lectures, comedy shows, and poetry readings is crucial. Some chapters have already begun this work, the New York City DSA-affiliated Sing in Solidarity Choir being a perfect example. In Boston DSA, a small group of comrades, including the writers of this article, have established the BDSA Artists’ and Musicians’ Caucus, through which we have begun to hold bi-monthly, free film screenings. Work such as this could very well lay the foundation for large-scale operations in the future.

Democratic Socialists of America

Democratic Socialists of America